The RESTful API has a funny place in the software development world: it’s widely regarded as the best general-purpose pattern for building web application APIs, and yet it’s also nebulous enough of a concept to cause endless disagreements within teams over exactly how to implement one.

Do I make my endpoint /company/123/ or /companies/123/? How about /companies/123/locations/ vs /locations/?company=123 ? How do I handle versioning the API? Why shouldn’t I send a POST request to trigger an action on the server? If a backend task can take many seconds to process, how do I represent that in the API?

Questions like these are asked and answered (in different ways) all over the Internet, and it can be frustrating to make sense of it all. In search of a better understanding of REST, I decided to go straight to the source: Roy Fielding’s year 2000 dissertation defining REST. What I found was not exactly what I was expecting, and yet I came away with a surprising amount of practical insights to apply to my API designs.

We’re going to walk through this paper chapter by chapter to see what there is to learn. Here’s a link to it in full if you’d like to follow along: https://www.ics.uci.edu/~fielding/pubs/dissertation/fielding_dissertation.pdf

Chapter 1: Software Architecture

The opening chapter goes to great lengths to define "architectural style" and related terms. While it makes for dry reading, it’s important, since there are subtle distinctions to make clear. In particular, what we would informally call "software architecture" is given the specific term "architectural style" here, and the term "software architecture" is reserved to describe a specific implementation of an architectural style.

The main motivation for this is to keep discussions of architecture well-grounded in the actual operation of the software, particularly with regards to data. "Box and line" architecture diagrams ignore data entirely, and so they don’t properly capture the behaviour of software. When we think of "software architecture" as an abstraction of the run-time elements of a software system, this makes explicit that different phases of a program’s operation (initialization, processing, shutdown, etc) might have different architectures, with yet another architecture responsible for transitioning between these phases. An architecture style, then, is a higher-level description of a "class" of software architectures.

For reference, here are all of these terms and their definitions:

software architecture : An abstraction of the run-time elements of a software system during some phase of its operation. A system may be composed of many levels of abstraction and many phases of operation, each with its own software architecture.

element : A software architecture is defined by a configuration of architectural elements—components, connectors, and data—constrained in their relationships in order to achieve a desired set of architectural properties.

component : An abstract unit of software instructions and internal state that provides a transformation of data via its interface.

connector : An abstract mechanism that mediates communication, coordination, or cooperation among components.

datum : An element of information that is transferred from a component, or received by a component, via a connector.

configuration : The structure of architectural relationships among components, connectors, and data during a period of system run-time.

architectural style : A coordinated set of architectural constraints that restricts the roles/features of architectural elements and the allowed relationships among those elements within any architecture that conforms to that style.

Chapter 2: Network-based Application Architectures

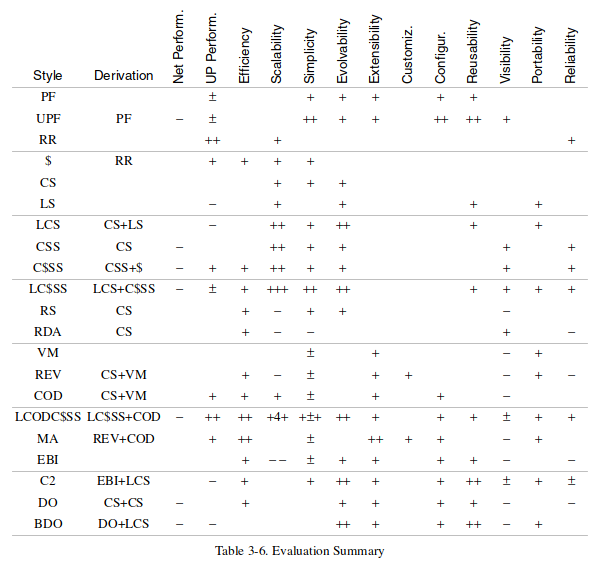

Next, Fielding defines a list of properties of architectural styles that are valuable or interesting, so that later we can evaluate a whole host of architectural styles against these properties.

The properties considered are:

- Performance:

- Network performance: Does it send a lot of data over the network?

- User-perceived performance: Does it have low latency? Does it render quickly?

- Network efficiency: Can it avoid using the network, e.g. via caching?

- Scalability: Can it scale to a large number of components?

- Simplicity: Is it easy to understand and implement?

- Modifiability:

- Evolvability: Can a component be changed without affecting other components?

- Extensibility: Is it easy to add functionality to the system?

- Customizability: Is it easy to override or specialize its behavior for unusual requirements?

- Configurability: Can it be easily adapted post-deployment?

- Reusability: Are its components generic enough to be reusable for other applications?

- Visibility: Is it easy to view the operation of the system externally?

- Portability: Is it portable across many runtime environments?

- Reliability: How susceptible is it to failure?

I think this list is such a fantastic set of evaluation criteria that it’s worth printing out and using as a checklist for any architectural task. The subtle distinctions between evolvability, extensibility, customizability, configurability and reusability are particularly handy; it’s entirely possible to make a super-extensible system that isn’t customizable, for example, or a super-customizable system that isn’t configurable.

Aside: Security

Reading this paper in 2019, one important property seems conspicuously absent from the list:

- Security: Will I get pwned by running this system?

It’s a window into a simpler time, to see security absent from a meticulous list of criteria used to evaluate systems which among other things send raw code back and forth between clients and servers. In this paper, security sees only casual mentions, and the ability for network firewalls to inspect unencrypted data over-the-wire is seen as a desirable feature.

While security should be a top consideration for any architecture today, REST stands the test of time by virtue of relying on the security of the underlying protocol on which it’s based (HTTP). It’s worth noting that it’s through other architectural properties that it has been able to achieve this: its evolvability allows HTTPS to be used, and its extensibility allows authentication/authorization to be layered on top of it by applications.

Chapter 3: Network-based Architectural Styles

With the evaluation properties defined, Fielding evaluates a range of architectural styles, unsurprisingly settling on a REST-like architecture as the winner. This is a hard chapter to summarize, so I’d recommend reading through it in full. Essentially, each style is given an acronym so that combinations of styles can be referred to by one big acronym.

Styles evaluated are (with very brief descriptions provided here when relevant):

- Data-flow Styles

- Pipe and Filter (PF)

- Uniform Pipe and Filter (UPF): For example, Unix command-line applications

- Replication Styles

- Replicated Repository (RR): Replicating data across multiple services

- Cache ($): RR variant where only requested data is replicated

- Hierarchical Styles

- Client-Server (CS)

- Layered System (LS): System organized into a hierarchy of layers

- Layered-Client-Server (LCS)

- Client-Stateless-Server (CSS)

- Client-Cache-Stateless-Server (C$SS)

- Layered-Client-Cache-Stateless-Server (LC$SS)

- Remote Session (RS): Application state kept entirely on the server

- Remote Data Access (RDA): Client performs database queries directly on the server

- Mobile Code Styles:

- Virtual Machine (VM): Executing code in a controlled environment

- Remote Evaluation (REV): Delegating expensive operations to a remote site for evaluation

- Code on Demand (COD): Component queries a remote server for the know-how to process a resource

- Layered-Code-on-Demand-Client-Cache-Stateless-Server (LCODC$SS)

- Mobile Agent (MA): Extension of RE and COD style where the agent performing computation “moves” from client to

server and back

- Peer-to-Peer Styles:

- Event-based Integration (EBI): components trigger and listen for events rather than integrating directly with other

components - C2

- Distributed Objects

- Brokered Distributed Objects

- Event-based Integration (EBI): components trigger and listen for events rather than integrating directly with other

Here’s the final evaluation summary from the chapter: each property has + or - characters proportional to a rough measure of how beneficial or detrimental the style is to that property.

The evaluation summary, in its full terse glory

In the end, we find that “LCODC$SS” appears to be the overall winner; that’s short for Layered, Code-On-Demand, Client Cache, Stateless Server. Sound familiar? With “layering” referring to gateways and proxies, “code on demand” referring to JavaScript, and caching/statelessness being common aspects of HTTP services, what we’re describing here is the Web as we know it.

This analysis not only provides the justification for the fundamental properties of REST as an architecture, but like Chapter 2, it’s a useful reminder of everything that’s out there for you to consider. Many of the architectures considered here have fallen out of favour, but that doesn’t mean they’re not still relevant today; every problem is different, and while REST works well for traditional web resources, it’s not the right tool for every job.

Aside: “Remote Data Access”

As a side note, I couldn’t help but notice that one of the mentioned styles sounded familiar…

The remote data access style is a variant of client-server that spreads the application state across both

client and server. A client sends a database query in a standard format, such as SQL, to a remote server. The server

allocates a workspace and performs the query, which may result in a very large data set. The client can then make

further operations upon the result set (such as table joins) or retrieve the result one piece at a time. The client

must know about the data structure of the service to build structure-dependent queries.

What’s this? How did GraphQL get into this paper from the year 2000?

It’s good to be reminded that some of these hot new tools are iterations on ideas that are decades old.

Chapter 4: Designing the Web Architecture: Problems and Insights

To expand on the general properties from Chapter 2, Fielding describes some further requirements that are specific to Web architectures:

- A low barrier to entry for everyone (readers, authors, and developers). Hypertext and HTML were chosen for this because:

- For users, it’s simple to navigate pages via hyperlinks;

- For authors, it’s simple to link to content, in particular because the content itself doesn’t need to exist yet in order to define a link;

- For developers, it’s simple to implement because all the protocols are defined as text, making them easy to inspect and interactively test.

- Extensibility

- Distributed content

- Internet-scale (in the sense that it needs to be tolerant of a chaotic Internet where network traffic is unpredictable and servers can be deployed/retired at will)

He also describes some of the additional challenges of trying to achieve these goals while building on top of the existing URI, HTTP and HTML standards rather than replacing them.

Chapter 5: Representational State Transfer (REST)

With all of that background out of the way, we finally turn to deriving REST itself. In proper scientific fashion, we start with a “null” architecture and build upon it using the constraints we’ve been laying out in previous chapters.

Deriving REST

The first two constraints are the client-server and stateless styles. Both of these are deemed necessary just due to the scale of the Internet: we keep implementations simple by separating the providers of the content (servers) from the consumers (clients), and we can’t afford to have servers maintain per-client state if they’re to work at the scale we envision.

The next constraint is caching: if we’re going to minimize network usage and user-perceived latency, we want an architecture that allows us to cache content effectively.

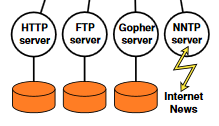

Before we go any further, let’s just admire the diagram displaying “Internet News” with a big exciting lightning bolt:

Back to constraints, we add “uniform interface” next. Fielding describes this as the core thing that differentiates REST from other architectural styles. REST ensures that every service works through a uniform interface, which aims to improve the simplicity and scalability of the architecture (at a modest cost to network efficiency). The constraints which achieve this uniform interface are described later.

Nearly finished with the constraining now! The penultimate constraint is layering: the ability to build hierarchical layers in the system to encapsulate or “hide” different layers. This enables a great deal of scalability, e.g. with load balancers spreading traffic across a number of servers, and it also provides the flexibility to evolve systems by

introducing layers to handle legacy servers or clients. The downside of layering is the extra latency/overhead, but we’re hoping that we can offset this with clever use of caching.

Finally, we’ve got code-on-demand: enabling (or at least not preventing) servers to supply code to clients for the client to execute. In the age of endless web apps this seems obvious, but I think it’s worth appreciating that this got factored in to Web specifications as early as it did. JavaScript was only a few years old at the time, and it wasn’t at all clear at that point that scripting would be an integral part of the Web.

REST Architectural Elements

Chapter 5.2 is where we finally define REST in concrete terms.

Many people jump straight to this section when trying to better understand REST, but this tells you the “what” without the “why” from the earlier chapters. Without understanding the derivation of REST, it’s easy to misunderstand the problems that REST aims to solve.

Here’s an overview of its architectural elements:

Data Elements

A resource is essentially any information that can be named, and a resource identifier is a means to access a resource (usually a URL). A key property of resources is that they do not necessarily have any direct correspondence with an underlying representation or storage location. For example:

- Two companies 1 and 2 might have similar identifiers (

/companies/1and/companies/2) even though their data resides on separate servers; - “Companies that user ABC has favorited” is a resource, even though it describes information which can change over time;

- “Currently active users” is a resource even though it’s constructed from live information that isn’t persisted anywhere.

While this is a simple concept, libraries like Ruby on Rails and Django Rest Framework make directly converting backend models into REST resources so easy that developers often fall into it as the default. This can create an undesirable coupling between client and server (where every backend database change requires a corresponding frontend change), and unnecessary frontend complexity (where clients collect and process raw data rather than rely on the server to present it to them that way).

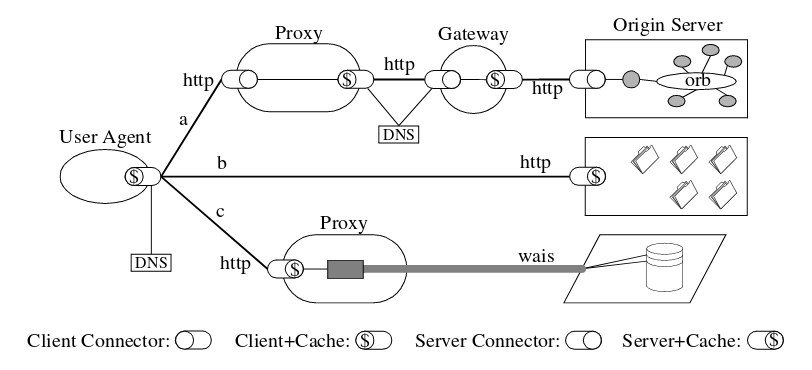

Connectors and Components

REST separates concerns with a variety of “connector” types: Client, Server, Cache, Resolver (i.e. DNS), and Tunnel (e.g. TLS).

A key aspect is the stateless communication between these connectors. Statelessness accomplishes four things:

- It reduces the resource requirements of the connectors

- It allows parallel processing of requests

- It allows an intermediary to understand a request in isolation, which is useful for dynamically modifying/reordering

requests - It forces all the information that’s relevant for caching to be present in the request

Overall View

With all these components in place, we have:

- User Agent which can submit concurrent stateless requests

- A DNS service which translates request URLs into addressable network locations

- The ability to have Proxies, allowing clients to access resources through an intermediate location

- The ability to have Gateways (i.e. reverse proxies), allowing servers to provided resources through an intermediate

location - The capability of introducing caching at any of these layers in order to avoid redundant network requests

As an example, we can model a Process View of a complex system, showing off what’s possible with the flexibility of this architecture:

Chapter 6: Experience and Evaluation

While interesting due to the historical context it provides, we’ll skip this section for today since most of the details here aren’t as relevant to modern-day systems.

Conclusions

Going into this, I was hoping to gain specific insights on building good RESTful APIs. What I got instead was insight into software architecture design in the very broadest sense. The bigger take-away from this dissertation, for someone like me at least, is not any particular detail about REST itself but rather the overall design process that created it. The evaluation criteria from Chapter 2 (performance, reusability, etc) and the architectural styles from Chapter 3 are as useful for defining your own architecture as they are for defining REST.

And while brushing up on these foundational REST concepts doesn’t directly answer any of those practical “detail questions” when building Web APIs, it’s… more immediately helpful than you might think. If you can’t recall why modifying state in response to a GET request is OK, you can “derive” the answer by remembering that a caching layer could stop repeated GET requests from hitting the server. If you’re not sure how to version your API, you can remember that both URIs and headers affect caching, so either way will do. If you’re not sure whether to choose /companies/123/locations/ as a resource vs /locations/?company=123, you can remember that resources don’t need to

have any relation to the underlying data, so you can choose whichever one is nicer to use in the client.

Perhaps most of all, it’s a good reminder that most of time when we developers debate what’s “RESTful” and what’s “not RESTful”, what we’re really debating is conventions. The flexibility of REST is the reason we have so much to debate, but it’s also the reason that REST is everywhere.

Image via https://pixabay.com/photos/fox-sleeping-resting-relaxing-red-1284512/