Spot the Vulnerability: Data Ranges and Untrusted Input

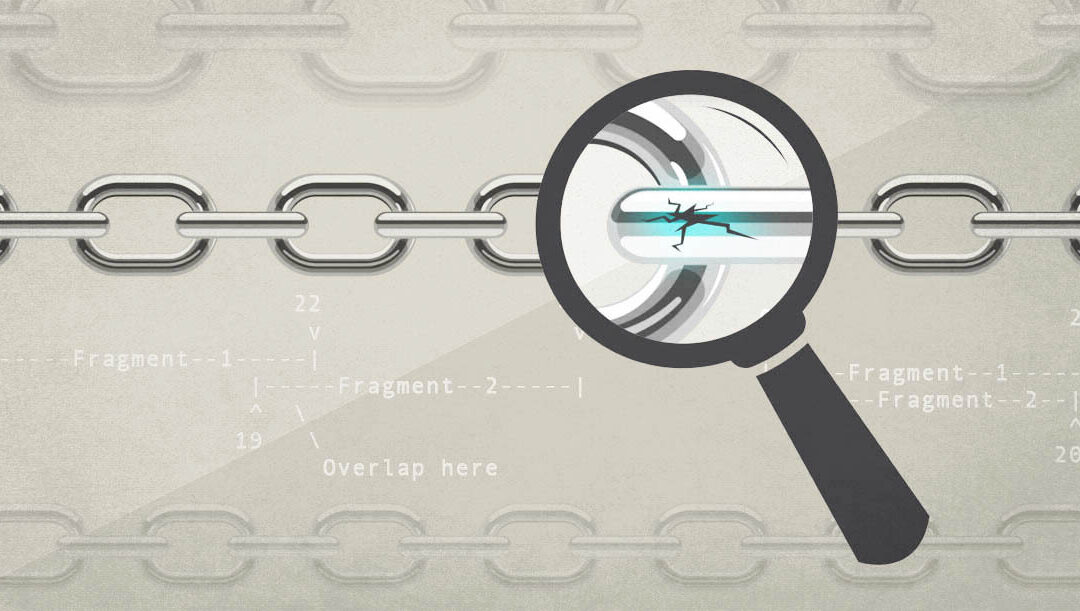

In 1997, a flaw was discovered in how Linux and Windows handled IP fragmentation, a Denial-of-Service vulnerability which allowed systems to be crashed remotely.

In 1997, a flaw was discovered in how Linux and Windows handled IP fragmentation, a Denial-of-Service vulnerability which allowed systems to be crashed remotely.

In the world of software consulting, it can be virtually impossible to determine what the fair market value for software development is. Nobody estimates work according to the same parameters: some firms have differing rates for differing services, some have offshore development services, some won’t provide a meaningful estimate at all (and for good reason).

Why do we always talk about unit tests? Why is “unit tests” automatically added to the plan of any or all projects? I think it’s just because it’s an expression we’ve gotten used to hearing. There are an awful lot of “xUnit” packages nowadays.

But what is a unit test, anyway?